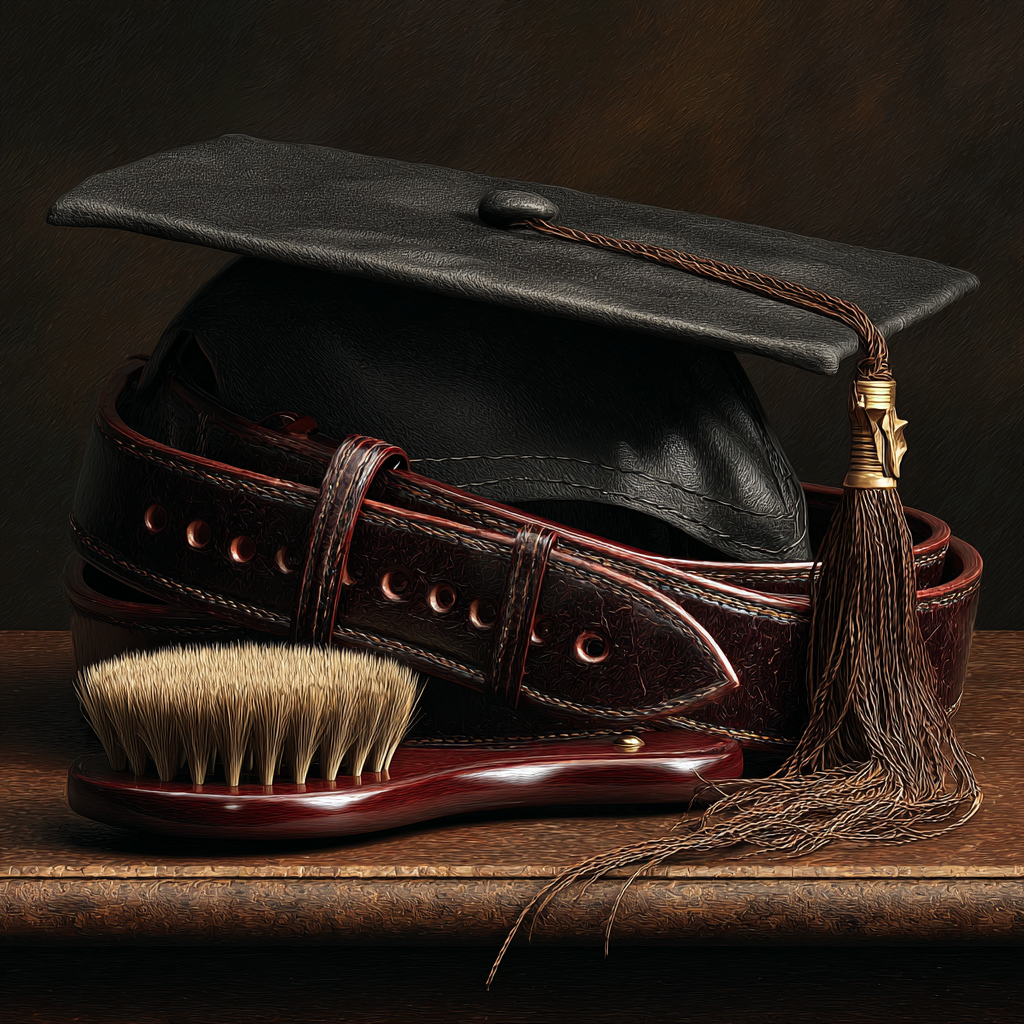

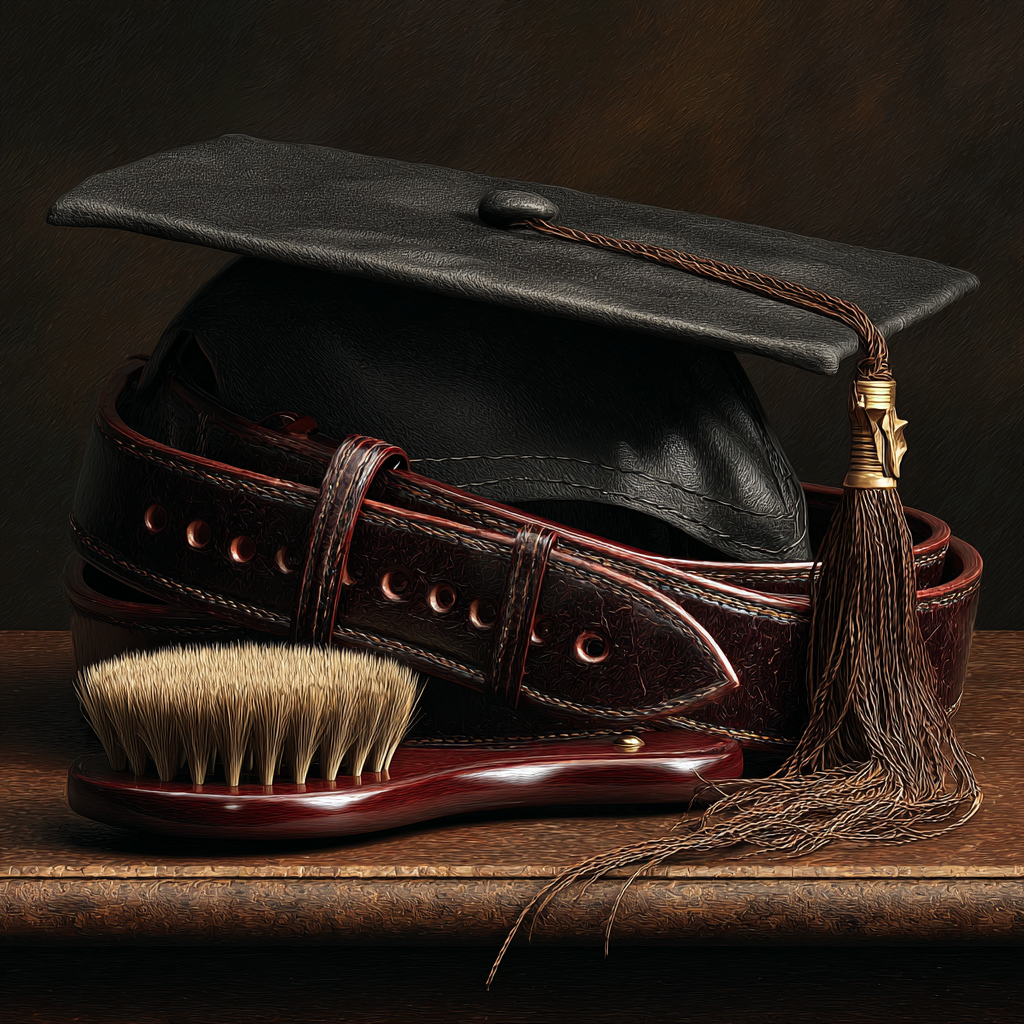

A struggling college student changes advisors and discovers that his new mentor has an unconventional approach to accountability.

Browse a diverse, curated collection spanning romance, drama, fantasy, and more. Whether you prefer classic discipline narratives or contemporary stories, you'll find something to enjoy.

Use the sidebar to browse by story title, author, or tag, and jump straight into what sounds fun.

A struggling college student changes advisors and discovers that his new mentor has an unconventional approach to accountability.

When nineteen-year-old Joanna's reckless night out goes too far, her aunt has strong feelings about it.

A strict governess oversees a punishment weekend for the wayward daughter of a wealthy mid-century family.

In Renaissance Venice, a young woman caught in scandal faces public punishment in St. Mark's Square.

Ferry worker Norah's quiet routine is upended when her partner Drew discovers a troubling lapse in judgment.